This is a series of five blog posts on Self-Directed Learning (SDL), which has become somewhat of a vogue term in the present educational context. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills identified SDL as one of the life and career skills necessary to prepare students for post-secondary education and the workforce.

In the previous post, the methodology for the systematic infusion and facilitation of metacognitive strategies was outlined and illustrated.

In this fourth post, the focus is on motivational strategies that can promote and sustain SDL. Although a whole host of research studies have shown the importance of metacognitive competencies in learning, it is widely accepted that metacognitive knowledge or regulation is not sufficient to promote student achievement. Students must also be motivated to use their metacognitive skills.

Infusing Motivational Strategies

What is Motivation?

Motivation initiates, directs and maintains all human behaviour. It is inseparable from learning in that without some motivational base, limited attention and effort will be given to that area of human activity. Indeed, as Sylwester (1998) pointed out:

It’s biologically impossible to learn anything that you’re not paying attention to; the attentional mechanism drives the whole learning and memory process. (p.6)

In a similar vein, Csikszentmihalyi (1990) argued:

The shape and content of life depends on how attention has been used….Attention is the most important tool in the task of improving the quality of experience. (p.33)

However, while motivation is recognized as fundamental to learning, there is much debate about how it works and, more significantly, how we as teachers can harness such human energy in the pursuit of educationally desired learning goals. The literature is rich in terms of theories and models of human motivation (e.g., Maslow, 1962; Herzberg, 1966; Deci and Ryan, 2002; Dweck, 2006), but I have some empathy with the frame of the management guru, Peter Drucker, who made the challenging assertion that:

We know nothing about motivation. All we can do is write books about it.

This may seem to have a fair measure of face validity in terms of widespread practice in educational institutions, as Levin (2008) concluded:

…boredom and lack of engagement remain endemic in schools around the world, and seemingly unmotivated students are a main complaint of teachers. (p.99)

Similarly, Wagner (2010) noted:

In countless focus groups I’ve conducted with high school students, “boring classes”- which include so-called advanced classes—are among the main complaints about school. (p.114)

It is not surprising therefore, as Gregory & Kaufelt (2015) concluded:

Motivation, enthusiasm, perseverance, drive, grit, and tenacity are currently hot topics in education. Understanding how to get students to pay attention and engage in rigorous tasks is something every teacher desires. (p.1)

In the context of metacognition, motivation is defined as “beliefs and attitudes that affect the use and development of cognitive and metacognitive skills” (Schraw et al, 2006, p.112). It has two primary components:

- self-efficacy, which is confidence in one’s own ability to perform a specific task

- beliefs about the origin and nature of knowledge.

The importance of students’ self-efficacy in their learning capability, and their beliefs about the nature of how humans learn and its basis (e.g., fixed or growth mindset) was identified in Blog Post 2.

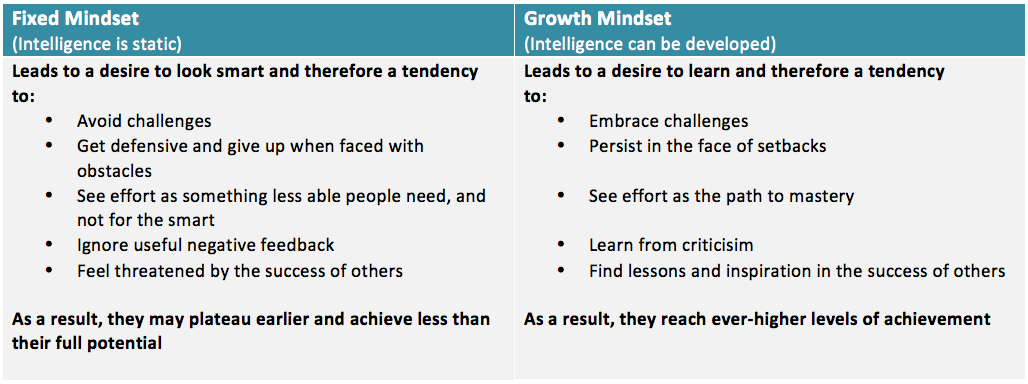

Dweck’s (2006) extensive research on students’ beliefs (mind-sets) relating to intelligence has profound implications in terms of motivation, how students subsequently approach their learning and for how teachers teach (see Table 1: Comparison of Fixed & Growth Mindsets). In summary, she contrasted two fundamentally different mind-sets relating to how students approach learning, a Fixed mindset and a Growth mindset. Students who possessed a fixed mindset tended to see intelligence as a stable genetic quotient and, therefore, you are either smart or you are not. In contrast, students who possessed a growth mindset saw intelligence as a more fluid entity, reflecting effort and hard work, and a capability that can be developed and enhanced.

|

Table 1.1: Comparison of Fixed & Growth Mindsets

Developing a Growth Mindset in students is especially important as Saphier (2017) concludes that the evidence suggests that the variables that appear to have the most significant impact on a person’s development and achievement extend well beyond any measurement of innate intelligence. He identifies that:

These variables appear to include the quality and quantity of schooling one experiences, the amount and kind of effort one invests, and the beliefs one holds in the individual’s capability to grow ability itself. (pp.30-31)

Most significantly, and specifically, as Schunk & Zimmerman (2012) point out:

…unless people believe that their actions can produce the outcomes they desire, they have little incentive to act or to persevere in the face of difficulties. (p.113).

It is not difficult to understand how beliefs profoundly affect the way people approach their learning and the subsequent impact on attainment levels. Beliefs act as major neurological filters that determine how we perceive and respond to external reality (the world around us and the people in it), and as Henry Ford famously wrote:

If you think you can or think you can’t, you’re right

However, here’s the really big point—as Adler (1996) cleverly noted:

We forget that beliefs are no more than perceptions, usually with a limited sell by date, yet we act as though they were concrete realities. (p.145)

How to Change Beliefs—especially those that limit motivation, learning & well being

Just as beliefs originated as perceptions, they can be changed by new perceptions that significantly challenge the existing beliefs. As a kid I believed in Tooth Fairies, Father Christmas and the Bogeyman under the bed. Since I sawed the legs off my bed, I’ve stopped believing in the latter. Just joking – and I think you will have made the relevant inferences and interpretations by now.

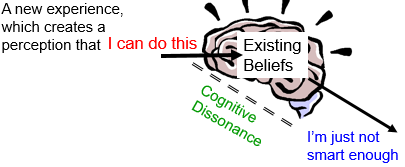

Invariably, people can be highly resistant to belief change, especially to deeply held ones that define life meaning and personal identity. However, in many cases, it can be a quick process when a new experience significantly challenges the belief and creates Cognitive Dissonance (i.e., a real challenge to the reality/validity of the existing belief). Fig. 1: Simple model of Cognitive Dissonance illustrates how this can happen.

|

Fig. 1.1: Simple model of Cognitive Dissonance

For many years, I worked in educational institutions where many students had little belief in their intellectual capabilities, and perhaps even less in the usefulness of teachers to do much to help them. In this situation, my priority was always to bring about some reframing in their perception of themselves as learners, and this can only be achieved ultimately through them achieving mastery in meaningful learning tasks. However, one must first get some positive reframing on you as a person, not a wider construct on teachers per se. In working with students who have negative frames on schooling and teachers, I learned that there is little benefit in trying to convince them of the value of paying attention and learning academic stuff. Also, there is even less benefit in showing annoyance or losing one’s cool over their lack of interest towards academic learning. This only reinforces their existing perceptions and may even add some pleasure or novelty to the situation for them – not for you. Unless you can get their attention and build some rapport, and ‘prove’ some meaning to the learning experience, it’s going to be a tough time as Michelle Pfieffer learned in ‘Dangerous Minds’, 1995, an American drama film in which she faced a very challenging class, but eventually got their attention which made the difference. You can watch the film to find out how. How did I fare in these stakes? Well, you’ll have to read Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach, by your author here – to find out. I’ll say one thing, Michelle was prettier than me.

Strategies for Developing A Growth Mindset

There are many strategies to foster a growth mindset, and it may happen quickly, or it may take a while, and you may need some persistence; these include:

- Teach students about Mindsets and How Humans Learn

- Communicate Positive Growth Mindset Messages in everyday teaching

- Use instructional strategies that support Mastery Learning

- Use Teachable Moments to reinforce aspects of students’ learning experiences that support a Growth Mindset

Teach students about Mindsets and How Humans Learn

Teaching students the Principles of Learning (Saphier, 2017; Sale, 2015) enables students to understand how their minds work (in the context of learning as well as other areas of human experience), enhances their learning capability and, over time, empowers them to become self-directed lifelong learners. Saphier (2017) recommends that educators:

…Share with them teaching and learning strategies we use ourselves. By including them in the secret knowledge of teaching and learning strategies we give students choices, power, and license to control their learning.

Principles of learning should be explicitly taught to students as they can use them to be more powerful learners. (pp.114-15)

This can be further reinforced with Stories and Examples of success by personal effort – Yours, Others, Students. As Willingham (2009) argues:

The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories – so much so that psychologists sometimes refer to stories as “psychologically privileged,” meaning that they are treated differently in memory than other types of material. (p.51)

Communicate Positive Growth Mindset Messages in everyday interactions with students

In the previous post, to facilitate the developing of good thinking, I emphasized the importance of making the cognitive heuristics of the types of thinking explicit for students – visible – and through retrieval practice in a range of application contexts, this becomes part of the language of learning. The same pedagogic process is necessary to make growth mindset concepts visible and part of everyday classroom interactions. As Saphier (2017) points out:

It is through daily interactions in everyday classroom life that we can:

- Convince students that “smart” is something they can get,

- Show them how, and

- Get them to want to. (p.40)

Students pick up on our language codes, vocal tones, and body language and form both impressions of us as teachers (as people), and of course how they think we perceive them. Tomlinson (2005) captures this poignantly:

My students hear every message I send – whether overt or implied – about their capability to learn and succeed. (p.76)

Use Instructional Strategies that promote Mastery Learning

Teachers are often pressurized into completing the curriculum in a given-time. However, students who lack prior knowledge and/or skills often fall behind, have difficulties with subsequent topics, and risk becoming labelled (and may self-identify as) ‘weak learners’. Mastery Learning focuses on mastering a topic before you move on to a more advanced one. Hence, when students master the content, they experience a sense of being competent, which is fundamental to supporting a growth mindset as it provides direct experience that perseverance and effort lead to success. This also enhances the possibility of intrinsic motivation in learning the subject.

Facilitating mastery learning inevitably involves some differentiation in the instructional strategy but, with good pedagogic design and the thoughtful application of technology, it is an achievable and desirable educational goal.

Use Teachable Moments to reinforce aspects of students’ learning experiences that support a Growth Mindset

If the above strategies have been well implemented, students will be experiencing changes in their learning status (e.g., accomplishing tasks they thought were beyond their capability; feeling that they are building a greater understanding of the concepts being taught). We may assume that the development of self-efficacy is occurring at the level of student experience, and neurologically they are building solid mental representations in long-term memory. Essentially, this is how learning works, and students will know it, feel it, understand it, and that’s powerful for developing self-directedness as a learner.

This is a great time for a teachable moment. When students are experiencing that “ahah” feeling when mastering a new concept or skill, then you can remind them (even praise them) of the effort they have put in and how a better understanding/competence results. You don’t say, “see you are so naturally smart” – right! For retrieval practice and fun:

A teachable moment is the time at which learning a particular topic or idea becomes possible or easiest (adapted from Havighurst, 1952)

|

Epilogue for this Episode

This episode has focused on specific motivational strategies that are effective in developing metacognitive capability. It is part of a wider aim of developing self-directed lifelong learners. To achieve this, students must understand how learning develops as a human process and capability and how metacognitive and cognitive skills – thinking – significantly facilitates meeting their learning goals. Many other pedagogic methods and interpersonal skills contribute significantly to enhancing students’ intrinsic motivation in school contexts, and there is a rich literature here (e.g. Saphier, 2017; Alderman, 2008; Wentzel, 2013). Do keep in mind the assertion of Wlodkowski (1999):

…if something can be learned, it can be learned in a motivating manner…every instructional plan also needs to be a motivational plan. (p.24)

See the final post in the series…

References

Adler, H., (1996) NLP for Managers. Judy Piatkus, London.

Alderman, M. K., (2008) Motivation for Achievement: Possibilities for Teaching and Learning. Routledge, London.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., (1990) Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Row, New York.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M., (Eds.), (2002) Handbook of self-determination research. The University of Rochester Press, Rochester, N.Y.

Dweck, C. S., (2006) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Ballantine, New York.

Drucker, P., (1999) Quote. Available at: (http://thinkexist.com/quotes/peter_f._drucker/2.html Last accessed, 20th October, 2018.

Gregory, G. & Kaufeldt. M., (2015) The Motivated Brain: Improving Student Attention, Engagement, and Perseverance. ASCD, Alexandria, Virginia.

Herzberg, F., (1966) Work and the nature of man. World Pub. Co, Cleveland.

Levin, B., (2008) How to Change 5000 Schools. Harvard education Press, Cambridge.

Maslow, A., (1962) Toward a Psychology of Being. Van Nostrand, New York.

Schraw, G. et al., (2006) Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education, 36, 111-139

Saphier, J., (2017) High Expectations Teaching. Sage, New York.

Sale, D., (2015) Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer, New York.

Schunk, D. & Zimmerman, B.J., (2012) Motivation and Self-regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and Applications. Routledge, New York.

Sylwester, R., (ed.), (1998) Student Brains, School Issues. Skylight Training and Publishing Inc, Arlington Heights, IL.

Wagner, T., (2010) The Global Achievement Gap. Basic Books, New York.

Tomlinson C.A., (2005) The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, 2nd Edition. ASCD, Alexandria, Virginia.

Wentzel, K.R., (2014) Motivating Students to Learn. Routledge, London.

Willingham, D. T., (2009) Why Don’t Students Like School: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Wlodkowski, R. J., (1999) Enhancing adult motivation to learn: a comprehensive guide for teaching all adults. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

Dennis is a long time SoftChalk user and has conducted workshops for educators showcasing SoftChalk as a way to improve their lessons.

Leave a Reply