This is a series of five blog posts on Self-Directed Learning (SDL), which has become somewhat of a vogue term in the present educational context. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills identified SDL as one of the life and career skills necessary to prepare students for post-secondary education and the workforce.

In the previous post motivational strategies that can promote and sustain SDL were identified and illustrated.

This final post continues with strategy usage, focusing of cognitive strategies, and concludes with a summary frame on facilitating Agentic Engagement in students that enables the collaborative shaping of instructional environments and strategies with educators that best support their self-directed learning.

Developing Agentic Learners

Cognitive Strategies

You may (or may not) recall from the first and third posts, the relationship between metacognition and cognition, and the similarities and differences in terms of strategy use. Well, you can always skip back there and refresh the memory systems. The key points are:

- they are very much interrelated as part of a wider System of Thinking, and inevitably mutually dependent on each other

- the main difference relates to the goal or purpose of the task in hand. Cognitive strategies facilitate learning and task completion, whereas metacognitive strategies monitor the process.

Cognitive strategies are essentially the conscious mental activities/operations we do to solve a problem. In the context of learning, we often refer to them as thinking or learning tools. These often involve physical tools such as Mind-mapping or Thinking Hats but, as Ormrod (2011) points out, they are “…ultimately the things we do inside our heads—thinking” (p.135).

The analogy of a Toolbox is useful in that as with the use of tools in the physical world, the effectiveness of any cognitive/learning tool depends on its appropriateness to the learning task in hand and how well it is used. Poor thinking, limited knowledge and skills in application will typically produce poor results. The cartoon below captures the point in a poignant visible form and is close to home for my competence level in the domain of household DIY.

|

Hence, in selecting and using cognitive strategies, the following heuristic is helpful:

- What is my learning purpose (e.g., extracting information from text; organizing information from a variety of learning resources; building understanding; cementing mental models in long term memory)

- What are useful strategies for this area of learning (and ones I like/work for me)

- How to use the strategies effectively and efficiently

- When to use them for best results.

For example, I find mind-mapping very useful for writing research papers, as I can identify the key structure and content areas on one sheet of paper and do ongoing good thinking—critical, creative, metacognitive—to develop the paper content areas from this central advance organizer. However, there is a skill in doing good mind-mapping and one does need to know the subject domain quite well otherwise the mind maps can become no more than mazes, confusing rather than aiding thinking and learning.

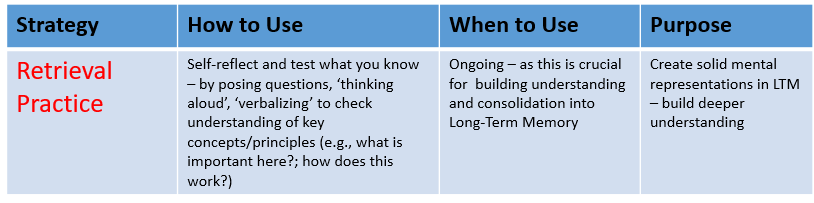

Another strategy that I introduce to students early in a course of instruction is Retrieval Practice (see Table 1.1: Retrieval Practice Heuristic). This strategy helps to build understanding and cement knowledge in Long-term memory (LTM). It involves students using their Working memory (WM) in response to a question posed internally or externally (e.g., what do I know about agentic engagement?) and searching LTM for what’s there (or not there). This is further enhanced when students engage in self-talk (talking aloud) and verbalizing with others as they can assess what they know already that’s useful, identify gaps and/or misconceptions, and take appropriate learning action (e.g., employ strategies if needed). The process of extracting what’s in LTM and subjecting it to scrutiny in WM, and then putting it back (often in an improved form—richer mental schemata) is a well validated strategy for effective learning from a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Repeated retrieval practice, especially when spaced out over time, builds the learning as a solid neural network and mental model for understanding. Hence future recall, when needed, becomes increasingly quicker, as well as more effective for connecting to new learning and enhancing understanding in that topic area.

|

Table 1.1: Retrieval Practice Heuristic

The infusion approach presented in the third post provides a guide for selecting and facilitating cognitive strategies across a course/module curriculum. Do remember that metacognition runs across the overall management of the learning process, proving the essential ‘quality assurance’ checks on the use of strategies and the overall self-regulation process.

Developing Agentic Learners

While teachers are tasked with designing and facilitating instructional strategies that engage students in the learning process and optimize their attainment opportunities, learning is also enhanced when students are actively involved in shaping the instructional process, making it more of a collaborative rather than one-way process. Reeve & Tseng (2001) referred to such student involvement as Agentic Engagement. This is where students take a conscious active role in shaping the learning context and instructional activities through collaborative learning relationships with teachers. Agentic Learners are confident to:

- Offer input into the lesson content (e.g., based on a diagnosis of what they are finding difficult and what might help their understanding for this topic area)

- Express preferences in terms of how they learn best (e.g., what methods/learning resources are most useful)

- Communicate their thinking or learning need (e.g., ask specific questions about what to learn and how)

- Communicate their level of interest (e.g., provide negative effort constructively when bored or frustrated

- Solicit resources to help their learning (e.g., feel comfortable in asking for help).

Agentic Learners can be framed as students who have learned how to learn and developed habits of mind (e.g., growth mindset) that support active engagement and autonomy in their learning relations and strategies. In becoming competent and confidence agentic learners, students need to have key understandings of how humans learn and are competent in using metacognition and cognitive strategies. In this way both the teacher and students thinking becomes visible and there is a shared language of learning as identified in the third post.

Empowering students with a Growth Mindset and Metacognitive Capability are major pedagogic interventions in helping students to be more agentic and develop their motivation and capability to move towards the long term aim of being self-directed lifelong learners.

An Autonomy Supporting Style (ASS) of teaching is also an extensively validated approach for facilitating students’ intrinsic motivation and agentic engagement in the learning process. Reeve (2015) frames ASS in terms of:

…a coherent cluster of teacher-provided instructional behaviours that collectively communicate to students an interpersonal tone of support and understanding, such as “I am your ally”; I am here to support you and your strivings… (p.407)

ASS is consistent with an Evidence-Based Teaching approach (e.g., Petty, 2014; Sale, 2015) and highly effective in building the collaborative and self-regulatory skills essential for developing SDL. EBT is derived from extensive research on what teaching strategies/methods work best in terms of learner attainment, and how humans learn most effectively. The key features of ASS include:

- Providing Explanatory Rationales to students on what makes this necessary

- Acknowledging & Accepting Negative Affect (e.g., students are tired/bored)

- Displaying Patience

- Exploring and allowing Student Choice (where possible) in the overall instructional strategy

- Encouraging Two-way feedback to support understanding and skill development.

As Treadwell (2007) argues:

One of the key aspects of increasing agency in school is having the learners take responsibility for their learning, where they can be aware of, and learn about, their mind-set and capacity to show ‘grit’ (determination). Learners in schools get the opportunity to ‘play’ with taking agency over their world and this is one of the most powerful learning lessons we can possibly gift them. (p.146)

Epilogue for this Series

In the first post, I made the case for Metacognitive Capability as the most important 21st century competence. Here’s my summary frame on this capability in terms of so-called 21st century competencies.

Lai & Viering (2012) noted that 21st Century Skills had become “watchwords in education” (p.2) and that many frameworks mapping such skills have been developed. Underpinning these frameworks and related to student attainment and positive learning and career development, 5 key research-based competences have been identified: Critical Thinking; Creativity; Collaboration; Motivation; Metacognition (Lau & Viering, 2012, p.6).

Research on these skills suggests they are interrelated in complex ways. For example, critical thinking and creativity are often expressed together. Metacognition is inevitably related to both critical and creative thinking and can be said to comprise ‘Good Thinking’. Similarly, motivation and metacognition are also reciprocally related as we have explored in some detail.

Hence, in conclusion to this series, I strongly recommend that teachers, school principals, educational policy makers and others involved in educational decision-making place Metacognitive Capability high on the agenda for curricula innovations seeking to enhance students’ self-directed learning. Such capability encompasses both knowledge on how to manage one’s thinking (e.g., critical & creative thinking), motivation (e.g., beliefs, emotions) and behaviour (e.g., collaboration with others), and the skills necessary to implement, monitor and evaluate strategy effectiveness in different learning situations.

References

Lau, E. R. & Viering, M., (2012) Assessing 21st Century Skills: Integrating Research Findings. National Council on Measurement in Education, Vancouver, B. C.

Ormrod, J. E., (2011) our Minds, our Memories: Enhancing Thinking and Learning at All Ages. Pearson, London.

Petty, G., (2014) Evidence-Based Teaching: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Reeve, J. & Tseng, C., (2001) Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (2011) 257–267.

Reeve, J., (2015) Giving and Summoning Autonomy Support in Hierarchical Relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 9/8, 2015, 406-418.

Sale, D., (2015) Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer, New York.

Treadwell, M., (2017) the future of learning. The Global Curriculum Project, Mount Maunganui, NZ.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

Dennis is a long time SoftChalk user and has conducted workshops for educators showcasing SoftChalk as a way to improve their lessons.

Leave a Reply