This is a series of five blog posts on Self-Directed Learning (SDL), which has become somewhat of a vogue term in the present educational context. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills identified SDL as one of the life and career skills necessary to prepare students for post-secondary education and the workforce.

In the previous post, through a review of the literature, I framed Metacognitive Capability as crucial to the development of Self-Directed Learning (SDL), and potentially the most significant so-called 21st Century Competence.

In this second post I outline, explain and illustrate an Evidence-based Pedagogic Framework for developing SDL. This is the underpinning theoretical rationale for the subsequent posts detailing the strategies to be used and how they work.

A Pedagogic Framework for Developing Self-Directed Learning

The Self-Regulation Cycle

Despite many approaches and models in the literature, there is general agreement that SDL (or SRL) involves the following iterative stages, irrespective of the specific terminology employed:

- Planning Learning

- Managing Learning Performance & Process

- Reviewing and Evaluating Learning

1. Planning Learning

As an old saying goes, ‘fail to plan, plan to fail’. This applies equally to learning almost anything. Essentially, when we seek to learn something new or extend our existing learning in some way, we are going about the business of enhancing aspects of our long-term memory system (e.g., in the language of neuroscience, building on existing neural networks in terms of the richness of pathway connections). Once established, this enhances our understanding of what we are intending to learn and, hopefully, our competence in applying this new learning skilfully in real world contexts.

Hence, in this planning stage, the learner (you, me, whoever) must do the necessary cognitive and metacognitive work and it’s necessary to have key underpinning knowledge on how we learn and how we think—as the latter involves the cognitive and metacognitive stuff.

Here’s a summary of the key areas/questions to address in the planning stage:

- Assess the task at hand and set key realistic goals for learning

- Identify interest/value (and personal strengths and weaknesses) for the learning involved

- Evaluate existing knowledge and skills to identify gaps, and how to address them

- Design a successful learning strategy (e.g., strategies to be used, when and how)

Set Key Goals for Learning

Research shows that academic performance gains range from 16 to 41 percent in classrooms where students are explicitly taught how and why it is important to set learning goals (Marzano 2007).

Goals are cognitive representations of a future event and, as such, influence motivation through five processes (Locke & Latham, 1990; Locke, Shaw, Saari, & Latham (1981). More specifically, goals, as Alderman (2008) identifies:

- Direct instruction and action toward an intended target. This helps individuals focus on the task at hand and organize their knowledge and strategies toward the accomplishment of the goal;

- Mobilize effort in proportion to the difficulty of the task to be accomplished;

- Promote persistence and effort over time for complex tasks. This provides a reason to continue to work hard even if the task is not going well;

- Promote the development of creative plans and strategies to reach them;

- Provide a reference point that provides information about one’s performance. (p.107)

Identify Interest/ Value and Personal Strengths & Weaknesses for the Learning Involved

We may like to achieve certain goals like getting fit, losing weight, etc. but often these don’t happen and there’s a reason for this. Motivation is multifaceted, and a number of aspects combine to influence the level of commitment and level of effort that one may put into goal attainment. Key aspects include:

- Interest in the tasks involved (intrinsic motivation)

- Value to the individual over and above intrinsic interest (e.g., usefulness for another extrinsic personal goal that gives a feeling of satisfaction)

- Cost-benefit analysis and Expectations that the effort required will lead to the perceived desired outcomes

- Beliefs about the nature of intelligence and what makes people successful learners

- Self Efficacy beliefs about one’s capability to be able to do what is necessary to achieve success

It is obvious that individuals are more motivated to engage in activities they find interesting. Whitehead (1967) puts a nice spin on this:

There can be no mental development without interest. Interest is the sine qua non for attention and apprehension. You may endeavour to excite interest by means of birch rods, or you may coax it by the incitement of pleasurable activity. But without interest there will be no progress. (p.37)

While interest may be situational or individual, it is the outcome of an interaction between a person and a particular piece of content—and therefore, while the potential for interest resides in the person, the content and the environment may determine the direction of interest and contribute to its development. However the big point, from a pedagogical perspective, is that interest is open to enhancement through pedagogic interventions.

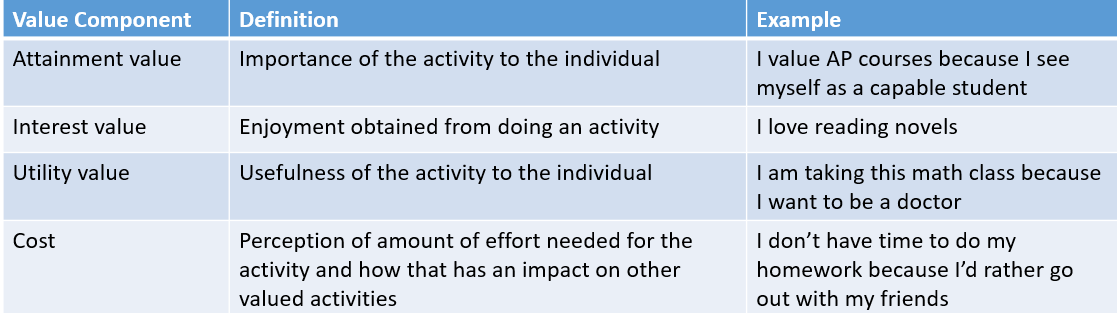

Value, apart from interest, also plays a part in the motivational stakes. While we may seek to develop a passion in learning (i.e., intrinsic motivation) for the subjects we teach (and this is a noble cause), we must recognize that there are equally powerful aims that are more extrinsic. Eccles and Wigfield’s Expectancy – Value Model (Table 1) captures the overall framing well:

|

Table 1: Eccles and Wigfield’s Expectancy – Value Model

Being honest with oneself about what you know and don’t know is important for effective learning. Also, this applies to evaluating one’s strengths and weaknesses, belief systems and ability to maintain volition in the learning process. A major area of motivational theory has focused on how attributions (what we believe to be true) impact student motivation and learning.

For example, Weiner (1992) summarized that how students attribute their outcomes (e.g., successes, failures) to such factors as ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck, have significant impact on how they orientate themselves to academic learning.

Most significant, in the present literature in recent years, has been the research by Dweck (2006) on the impact of a Growth Mind-set (as compared to a fixed Mind-set) on student learning and attainment:

…growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts. Although people may differ in every which way—in their initial talents and aptitudes, or temperaments—everyone can change and grow through application and experience (p.7)

Equally important are what Bandura (2004) refers to as Self-Efficacy Beliefs, which “are rooted in the core belief that one has the power to effect change by one’s actions” (p.622). As Pagares (2012) summarizes:

People with a strong sense of self-efficacy approach difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered rather than as threats to be avoided. They have greater intrinsic interest and deep engrossment in activities, and they set themselves challenging goals and maintain strong commitment to them. (p.113)

Hence, while a sizeable body of research demonstrates that students’ use of learning strategies promotes academic achievement (e.g., Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons 1990), research also indicates that student self-beliefs or efficacy to strategically regulate learning also play an important role in academic self-motivation (Zimmerman et al, 1992). Hence, developing students’ beliefs in their learning capability, and competence in using metacognitive and cognitive self-regulation strategies may result in a synergistic impact on academic achievement and intrinsic motivational engagement dimensions (e.g., cognitive and emotional engagement).

Designing a Successful Learning Strategy (e.g., strategies to be used, when and how)

Having the motivation to succeed is important, so are the beliefs that with effort and perseverance, success in many situations is possible. However, as Dweck & Master (2012) point out:

“…it is not sheer effort that produces effective learning. Students must also learn how to select strategies that will bring success and to alter their strategies when they are not working” (p.39)

The ability to use metacognition, selecting, using and evaluating cognitive strategies, is of key importance in terms of goal attainment and becoming a self-directed learner. It is for this reason that students need to understand how to use metacognitive and cognitive strategies effectively (e.g., what these are, how they benefit learning and how to use them effectively). In most basic terms, if we don’t know how to do something, we are unlikely to attain competence even with much practice. Students need to learn how metacognition works in the context of good thinking and how this is part of the process of effective learning.

2. Managing Learning Performance & Process

Good planning is crucial, and we have outlined the key components above. However, the best plan in the world does not mean success without the appropriate action—right? In teaching, a great lesson plan enacted by a poor teacher is likely to have little impact in terms of desired learning.

In this stage of the self-regulatory process, metacognition focuses on the use of cognitive and motivational strategies to ensure the successful maintenance of the overall learning strategy towards goal attainment. Hence, it is important to be mindful of

- Ensuring the necessary effort is put into the implementation of the cognitive learning strategies employed. Unless they are implemented effectively and conscientiously, there may be little benefit in terms of the learning benefits they might have facilitated.

- Maintaining a Growth Mindset. We are fragile creatures and can easily slip into self-doubt and loss of confidence. This happens to even the best sportspeople, so us mere mortals had better be mindful.

Expect challenges and setbacks that may seem to push you backwards in what you are learning. This is where self-control and willpower come into play. As mentioned, we have limited amounts of willpower and distractions are all around us. As Colvin noted:

If the activities that lead to greatness were easy and fun, then everybody would do them, and they would not distinguish the best from the rest. (p.72)

As we will see, in latter posts, different strategies are useful for different learning purposes. This is a bit like a toolbox; one must know the affordances and limitations of different tools and be able to select the best ones for the task in hand.

3. Reviewing and Evaluating Learning

This process is in operation throughout all stages of the Self-Regulation Process. It is a key component/activity of Good Metacognition, as we are evaluating both our thinking processes as well as other aspects of being (e.g., beliefs, emotions; and moods) that impact Self-Regulation. Key questions to answer truthfully (as far as is possible) are:

- Have I met the goals I set out to achieve (‘spot on’, more, less)—what is the evidence? You need to be as honest and open as possible on this—good feedback is crucial.

- How effective and efficient have I been in this learning process—what strategies have worked (not worked), how well?

- What do I now need to modify/change and how might I get this moving as effectively and efficiently as possible?

As in all skill development, this will require good understanding, practice and perseverance; but with the right strategies, competence will develop over time.

Epilogue

To develop an effective approach to developing SDL, all components of this framework need to be addressed thoughtfully in the context of the student profile. As an analogy (not a perfect one, but ok for this illustration), think of the mind like a car, which is a system and, if we don’t know the parts of the system, what they do and how they work, and their relationship to each to the other, we are like the poor chap in this cartoon:

|

This resonates with me, as I have no competence in car maintenance. However, I do not get into this situation, as I know that I know nothing about motor vehicle maintenance and have no interest in this area, so I behave intelligently (i.e. metacognitively) and ring my mechanic who somehow knows how to fix it.

If our aim is to develop students’ capability to become self-directed learners, we must teach them what it is, how to do it, and what makes it useful for meeting their goals. This entails providing them with the essential knowledge, strategies and application opportunities through good practice over time. On the motivational stakes, we can only provide the opportunities and rationale. It’s ultimately their call.

In the forthcoming posts, it’s all about the strategies to develop Metacognitive Capability—hope you are still up for this—it’s a question of motivation and volition… everything is!

References

Alderman, M. Kay. (2008) Motivation for Achievement: Possibilities For Teaching And Learning. Routledge, London.

Bandura, A. (2004) Swimming against the mainstream: The early years from chilly tributary to transformative mainstream. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 613-630.

Dweck, C. S., & Master, A. (2012) Self-Theories Motivate Self-regulated Learning, in D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman, Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research and Applications. Routledge, New York.

Marzano, R. J. et al., (2007) Designing and Teaching Learning Goals and Objectives: Classroom Strategies That Work. Marzano Research Laboratory, Colorado.

Pajares, F. (2012) Motivational Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Self-Regulated Learning, in D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman, Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research and Applications. Routledge, New York.

Zimmerman, B.J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990) Student differences in self-regulated learning: relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 51-59.

Zimmerman, B.J. et al (1992) Self-Motivation for Academic Attainment: The Role of Self-Efficacy Beliefs and Personal Goal Setting. American Educational Research Journal, 1992, Vol. 29, No.3, pp 663-676.

Weiner, B. (1992) Human Motivation: metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, C.A., Sage.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

About Dennis Sale: Dennis Sale is the author of Creative Teaching: An Evidence-Based Approach (Springer, 2015), the first book to demystify creative teaching and make explicit how it works at the level of specific teaching practices, underpinned by the creative application of cognitive scientific principles. He has worked in all sectors of the British education system, spending some 3 decades training and mentoring over 3000 teaching/training professionals in many countries and cultural contexts. Presently he is Senior Education Advisor for Singapore Polytechnic, and Principal Investigator for a 2-year Ministry of Education research project, entitled ‘Enhancing Student’s Intrinsic Motivation: An Evidence-Based Approach’.

Dennis is a long time SoftChalk user and has conducted workshops for educators showcasing SoftChalk as a way to improve their lessons.

Leave a Reply